Women’s rights in society have been discussed for decades. Questions about rights to vote, right to work, right to choose whom to marry, and right to abortion have all been considered in countries around the world. Each of these questions indirectly addresses whether providing basic human rights to women is important. As of now, in the developed world, most people agree that women should be provided with these rights (if they do not already have them) and that these rights should be preserved and protected for women. Another question addresses women’s right to serve their country by doing military service. In several countries, including the United States, the discussion has transitioned from a discussion of whether women should even have the right to perform military service at all to whether women should have the right to serve in combat units.

Different Practices Based on Different National Opinions

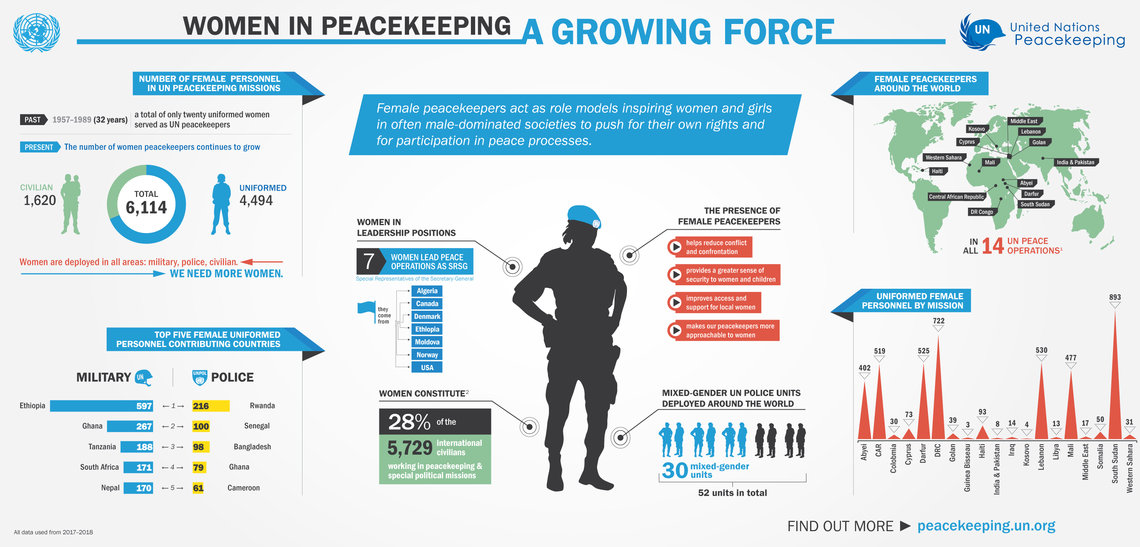

Several countries have acknowledged for years that women have a right to serve in the military, and some countries like Denmark, Norway, and Sweden have further acknowledged that women have the same rights as men when it comes to serving in a combat unit.[i] It is important to be aware that opinions differ at the national level; thus, some nations have allowed women to serve in combat units, and some nations have not. Some nations have granted this right for purely short-term political reasons; it was a politically necessary campaign issue at the time of one or more elections. Some nations have allowed this because of a small population; they need everyone to contribute in some way. Some nations have done this because of long-term political reasons, based on overarching national policies or international policies, such as United Nations resolutions. But few nations have opened military service to women based upon an analysis of military necessity or whether a mixed distribution of gender in all units will enhance the effectiveness of the military organization.

What Value Does Mixed Gender Distribution Add to Military Organizations?

Based upon a combination of what I know about the current conflict environment and my personal predictions about the future conflict environment, I find the question of whether a mixed distribution of gender adds value to military organizations to be highly relevant. Since men have historically been allowed, and sometimes required, to serve across the entire military organization, the actual question here is what difference, if any, adding women to the mix will make.

Do women only add value? Do women only subtract value? Is it that black or white? In my opinion, the answer to these questions is not that simple. Given the range of military specialties, I do not think it is possible to argue that women in the infantry, for example, will always add or subtract the same value as women working in logistics. Along the same lines, it does not seem fair to argue that the same value always will be added or subtracted by women working in staffs that develop overarching joint and interagency policies when compared to women working in staffs that develop tactical plans covering fire and maneuver at the battalion level. There also appears to be a difference in the value added by a female general leading a coalition of forces in a stability operation versus a female general leading an army in an existential war against a highly capable enemy. I am not arguing—at least not yet—that gender adds or subtracts any particular value while filling these different positions. I do think that there is a difference in the impact of women’s military service, depending on where they are assigned to serve.

Cohesion—A Tricky Concept

The question of the impact of women’s military service is connected to the concept of cohesion, which is important for most organizations to function smoothly. Cohesion is a tricky concept because it is challenging to measure, it can change over time, and it concerns both the individual and a group. Cohesion is connected to culture, which has many of the same attributes as cohesion. Academics define culture in numerous ways, and there is no universal understanding of what the concept of culture—or cohesion for that matter—consists of. There is some agreement that culture is connected to values, and since different people have different values, there will be different cultures. This applies to a military organization: even though the military can select its personnel and shape a social group to a larger extent than other organizations and cultural groups, different cultures can exist within different military units based on the different values of the members of these units. Cohesion forms in different units based on different things, and likewise, cohesion can be ruined or degraded by factors that differ across units.

In an infantry unit, where the core values often are related to being effective, masculine, tough, strong, just, and unaffected when facing an enemy at close range, cohesion is generated and degenerated in ways that differ from how cohesion is generated in a logistics unit, where the core values often are related to being effective, precise, solution-oriented, cooperative, and supportive when providing logistical support to own forces. Cohesion forms and degenerates still differently in a Special Operations Forces unit as well. The values of a unit will define its culture, and since culture and cohesion are interconnected, the values are what determine whether cohesion forms. That is why I believe it is possible to integrate women in many military units, without degenerating cohesion to the extent that the net value added is negative. I actually believe that cohesion will increase in some cases. But at the same time, we must be honest enough to admit that in some units it is not possible to produce this positive effect. But in my opinion, that is not (or at least, should not be) the case for Special Operations Forces.

Do We Need a Mixed-Gender Organization?

I personally believe the following: women and men should in general have the same rights; it is healthy for most environments and organizations to have a balanced mix of men and women; keeping relevant standards is important for the military; women and men should be held to the same standards if they do the same job; and it is possible for women to meet SOF standards. It is important for some nations in the developed world to be good role models for implementation of resolutions like UN 1325, [ii] which addresses Women, Peace and Security, to make other countries adopt it in a relevant manner. Military necessity in the existing security environment and the potential for a more effective military organization should be the deciding factors for whether women should be able to serve in combat units. If, after a rigorous analysis of these factors, the net sum of value added and subtracted is positive, then women and men should be permitted to serve together in the same units.

I suspect that not many people would disagree with me on that count. If a new type of organization is more efficient than another, then it is foolish to continue using the old construct. Therefore it is quite interesting for me to see that the current debate often bypasses foundational questions covering military necessity in a more or less elegant manner.

There appears to be a lack of interest in acknowledging the fact that a military organization needs women to meet the challenges in the existing environment and that a mixed gender organization will then indirectly make the military more effective. The current debate addresses questions that seem to me to be childish, populist/tabloid, and of a character that is not appropriate for an important discussion like this one.

The discussion of women in the military

Instead of being based on relevant analysis of identified operational requirements, the current discussion just drowns in a pool of arguments that I find damaging for both the debate and the development of a more efficient military.

To better explain myself, I would like to provide a caricature of the current debate. On one hand, there are arguments made by mainly angry, middle-aged white men saying that women are not strong enough physically or psychologically, have menstrual periods, and ruin cohesion in units because all men view women as sexual objects first and human beings next, and because men will not be able to operate effectively with women present. On the other hand, there are arguments made by middle-aged women of all shapes, sizes, and races, who often have no desire to serve in the military, arguing that women by principle should have the same rights as men, and that alone should force the military to have a 50-50 gender representation in its organization. Some of these women even argue that, since women have been excluded from military service for so long, they should be given special benefits and held to different standards—meaning lower standards—than men when they do military service. Both sides in this debate seem to be more emotionally invested in keeping women out of the military or getting women into the military on principle, than actually considering what is best for an efficient military organization for the future.

The Current Security Environment vs. Future Security Environment

The current security environment is more complex than that of the past. Today’s militaries encounter asymmetric conflicts of unconventional, irregular, hybrid, and sometimes, conventional character.[iii] Several academics and military officers have tried to explain what the environment currently consists of and what to expect in the future. Most of these explanations have been criticized in some way. Some have been accused of focusing too much on the European context, some have been accused of being too focused on the irregular context of warfare, some have been criticized for focusing on old tactics while discussing the current battlefield, and some have been accused of being too focused on new domains and technologies. Nevertheless, from a NATO point of view, I find all of these perspectives relevant for gaining situational awareness of both the current and the future security environment.

The Current Security Environment

The explanations for why the current environment is more complex compared to the past are many. William Lind describes his view of modern war and the current conflict environment: modern conflicts are smaller and more local, more culture-based, more diverse, and more political than earlier conflicts.[iv] At the same time, Lind acknowledges that not everything is new, innovative, or unprecedented when investigating the tactics now in use. Indirectly supported by retired General James Mattis,[v] Lind argues that many of the tactics that may be defined as new by some people are, in fact, rather old tactics—some as old as the concept of the nation-state—reappearing in what he defines as the fourth generation of warfare.[vi]

The retired British general Sir Rupert Smith argues in his book, Utility of Force, that lately there has been a paradigm shift in warfare, from wars mainly between nation-states, described as “interstate industrial wars,” to a “war amongst the people.” Smith highlights six areas where it is possible to divide the two paradigms:

- The ends we fight for have changed.[vii]

- The fighting is now conducted where people live.[viii]

- The conflicts seem to never face an end.[ix]

- The conflicts consist of mostly non-state actors.[x]

- Some actors are not willing to do what it takes to win a conflict.[xi]

- Weapons systems and ways of organization, developed for interstate industrial war, are applied to the new paradigm.[xii]

The Future Security Environment

The famous Danish scientist Niels Bohr is known for saying, “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.”[xiii] With my limited capacity, I am quick to acknowledge that predicting future events can be challenging. Nevertheless, some acknowledged academics have tried to do so, and I now present three different future predictions to show that the future security environment represents challenges beyond what we have acknowledged in the past.

David Kilcullen

In his book Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerilla, David Kilcullen points out four trends in his attempt to predict what the future conflict environment will look like. Urbanization, severe population growth, littoralization, and enhanced connectedness in underdeveloped countries are the trends that he believes will affect the conflict environment the most.[xiv]

John Arquilla

In his book Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits: How Masters of Irregular Warfare Have Shaped Our World, John Arquilla conducts a historical analysis of a number of wars that had an irregular character. His assessment, is that future fights “are more likely to take an irregular hue,”[xv] and that “conflicts will unfold largely along irregular lines, in either the physical or virtual world, or both.”[xvi] Arquilla argues that there are five related pairs of concepts that shape the irregular conflicts of today and that these will continue to shape the future in important ways.[xvii]

These concepts are:

- transformation and integration,[xviii]

- cooptation and infiltration,[xix]

- narratives and nation building,[xx]

- networks and swarming,[xxi] and

- deep strikes and infrastructure attacks. [xxii]

To be able to succeed in future conflicts, a deep understanding of how to employ the mentioned concepts is needed. [xxiii]

Martin Van Creveld

In his book The Transformation of War, Martin Van Creveld predicts the future security environment to consist of mainly low-intensity conflicts. Future low intensity conflicts will represent significant challenges compared to what the world is prepared for. Creveld argues that the future security environment will need other types of military organizations beyond those that exist today. The world will have to face an intermingled fight that will be rooted in a population,[xxiv] not fought by militaries but by fanatical ideologically-based organizations.[xxv] The security organizations for the future fight therefore need to be of an unconventional character and must be prepared to participate in an intermingled fight on behalf of a political community instead of a conventional military.[xxvi] These conditions lead to a number of changes, or developments, beyond the earlier conventional understanding of the security environment and its conventions of warfare.

How Does the Environment Relate to Women in SOF?

From the descriptions of the current security environment and the predictions of the future environment presented so far in this article, it is obvious to me that including women in the organizational mix will add value and make the military more effective. While adding women may not make the military more effective in every setting or situation, I am confident that the net sum will be positive. By not integrating women, we will limit our military’s effectiveness. We should make serious effort to make the internal cultural transition/shift—which is necessary if someone is in doubt—and integrate women into relevant roles.

The Current Environment

Rupert Smith described the current security paradigm as “war amongst the people,”[xxvii] a fight for new ends,[xxviii] never-ending conflicts,[xxix] conducted by non-state actors that are willing to do what it takes to win,[xxx] versus some actors that are not willing to do what it takes to win.[xxxi] Lind described modern conflicts to be “smaller and more local, more cultural based, more diverse, and more political than earlier conflicts.”[xxxii] Almost half of the world’s population consists of women.[xxxiii] Some cultures prohibit interaction between men and women, and some cultures do not allow women to contribute officially in politics but give them significant roles in other aspects of society. By not having women represented in our military organization, we will limit our own reach in the current security environment as described by Smith and Lind.

The Future Environment

If we look at the future security environment, the limitations in the military organization will most likely be even more obvious. World population is expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030 and 9.7 billion by 2050.[xxxiv] The anticipated growth in the world’s population is in line with David Kilcullen’s predictions about the future conflict environment.[xxxv] The other trends he identifies—urbanization in littoral areas and enhanced connectedness[xxxvi] —are also limiting military effectiveness if our fighting force lack women. John Arquilla’s argument about networks and swarming makes it even clearer that we are limiting ourselves.[xxxvii] Without integration of women, our own network is limited in many situations, which indirectly limits our potential access to an opponent’s network. This also points back to what Arquilla argued in regards to transformation and integration,[xxxviii] cooptation and infiltration,[xxxix] narratives and nation building,[xl] and deep strikes and infrastructure attacks.[xli] It is important to have a relevant fighting force, and in the future, women will be an important component in the “skillful blending of conventional and irregular troops and operations,”[xlii] which according to Arquilla is a key characteristic. Having women integrated and operating in relevant roles within our fighting force will provide the military organization with new ways to infiltrate other networks or organizations; new possibilities when it comes to recruiting potential proxies; access and cover in the new types of terrain, and thereby indirectly an increased mobility and an increased reach for deep strikes and infrastructure attacks; and new ways to communicate a compelling narrative to a larger audience.

Martin van Creveld’s future prediction also calls for a military organization consisting of both men and women. The low intensity conflict–type of intermingled fight he describes will require unconventional and innovative approaches conducted by people who are willing to go to the limits of their personal and professional morale to get the job done. No one will be protected for the new types of conflict.[xliii] According to van Creveld, in the future, a strategy will still be necessary to win a war, even though it may be more challenging to construct.[xliv] Understanding a potential enemy will be essential to producing a relevant strategy for outwitting and deceiving an enemy in order to win a future fight. For example, a recent Council on Foreign Relations analysis of 30 countries shows that, because women are substantially more likely than men to be early victims of extremism, women are well positioned to detect early signs of radicalization.[xlv] This kind of information and understanding is highly relevant to appreciate when constructing future strategies. So, without a female perspective while building understanding, and without the ability to relate to a large portion of a population, strategists could produce a more limited strategy than they would if women figured in the analysis.

The future demands a military capable of conducting policing operations,[xlvi] not only high intensity warfare. This also requires women in the organization to exploit its full potential, that is, if the military takes policing responsibilities seriously. The military must be able to help, support, and interact with the population as a whole, and without female presence, it will not be possible, especially in locations where the local culture limits the interactions between men and women.

While conducting these types of policing missions, new types of technologies and tactics must be applied. It will not be acceptable, or desirable for that matter (at least from a strategy perspective), to employ expensive and overwhelming/massive weapon systems while fulfilling a policing function. Instead of avoiding risk to the warfighter’s own personnel by killing people from a distance, in a classic 2001–2005 counterinsurgency fashion, future warfighters might have to be willing to accept personal risk and interact with people in a police fashion. By accepting the fact that police-type missions and interactions will be more important in the future, the military indirectly accepts a higher risk. Situational awareness and understanding of the population will become even more important than ever, especially related to personal security for the members of the force. Even though it is likely that future conflicts will include tactics like improvised explosive devices, assassinations, and the use of child soldiers, the willingness to gain information and an advantage in situational awareness must be something to work toward. It is clear that women integrated in relevant roles in the force might help us gain that advantage.

What Are Relevant Roles?

Martin van Creveld has argued that women have no relevant function in the military.[xlvii] Nevertheless, in his prediction of the future, he states that the intermingled fight which is to come “will affect people of all ages and both sexes.”[xlviii] Further, he argues that “in vast parts of the world no man, woman, and child alive today will be spared the consequences of the newly-emerging forms of warfare.”[xlix] My understanding of this prediction is that everyone will potentially be affected and that everyone can potentially contribute to the fight in some function or role. According to David Tucker and Christopher J. Lamb in their United States Special Operations Forces, “there is no compelling evidence that women in SOF will make SOF more effective.”[l] But they also argue that it might be beneficial to have women in designated roles and functions, such as Civilian Affairs and PSYOPS.[li] So, from this, it is clear to me that there is a huge potential for women’s participation within Special Operations Forces and its mission-set. There are several roles where women can add value, and the culture in SOF should be more open to women compared to other units, based on general values promoted by SOF.

Humans are more important than hardware. People—not equipment—make the critical difference. The right people, highly trained and working as a team, will accomplish the mission with the equipment available. On the other hand, the best equipment in the world cannot compensate for a lack of the right people.[lii]

Quality is better than quantity. A small number of people, carefully selected, well trained, and well led, are preferable to larger numbers of troops, some of whom may not be up to the task.[liii]

With values like these as a foundation, SOF culture should be able to integrate women if they are able to get the job done.

A Comparison of U.S. and NATO Doctrine

It is important to be aware that NATO Special Operations Forces doctrine and US Special Operations Forces doctrine differ slightly. Both doctrines recognize that SOF consists of specially selected, trained, educated, and equipped personnel; SOF operations can be applied throughout the whole spectrum of conflict; and SOF operations can be independent or in combination with conventional operations in order to fulfill strategic effects. But unlike U.S. SOF doctrine, NATO doctrine scales operations based on intensity, with the underlying assumption that peace and conflict are cyclic conditions. U.S. doctrine scales operations based on purpose, themes, or functions. The resulting difference is that NATO SOF doctrine, Allied Joint Doctrine for Special Operations (AJP-3.5),[liv]outlines three core tasks for SOF—Direct Action (DA), Special Reconnaissance (SR), and Military Assistance (MA)—while U.S. SOF doctrine, Special Operations (JP 3-05),[lv] outlines a higher number of thematic and functional operations as SOF core tasks—SR, DA, Counterterrorism (CT), Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction (CWMD), Counterinsurgency (COIN), Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Foreign Internal Defense (FID), Security Force Assistance (SFA), Unconventional Warfare (UW), Civil Affairs Operations (CA), and Foreign Humanitarian Assistance (FHA).

This different doctrinal approach and the difference in size of U.S. and NATO SOF allows U.S. SOF to assign different SOF units to one or more of the specialized doctrinal tasks, but this is not the case in most NATO countries, where SOF units often focus simultaneously on all the doctrinal tasks. The distinction between combat units and support units within SOF is not as evident in NATO as it is in the United States. Even though the distinction between combat units and support units within U.S. SOF is less noticeable today than it was earlier, it still exists,[lvi] which may make it more challenging to integrate women into all the roles that the situation actually requires them to fill. The current divide between combat units and support units makes it much easier to keep the women in support units even though there are roles in combat units that are suited to women. This is not automatically the case in several NATO countries.

Based on a short analysis of what the doctrinal tasks consist of, historical examples, and discussion of what the current and future security environment will demand of SOF, this article further highlights different roles that women should fill within NATO SOF in order to become “a capability that, when added to and employed by a combat force, significantly increases the combat potential of the force and thus enhances the probability of successful mission accomplishment”[lvii]—also known as a force multiplier.

General History of SOF in NATO

Most SOF units in NATO countries originated during the Second World War. Many countries phased out their SOF units when WWII ended, just to reestablish them a decade or two later. The general public opinion after WWII was that women should not be members of the armed forces because it was a man’s job. The SOF units established after WWII were established by men for men, which led to a homogenous environment. As highlighted earlier in this article, the security environment and the ways wars are fought have changed since then. It is quite clear to me that the homogeneous, masculine, secretive SOF environment has produced social constructs,[lviii]which has limited SOF’s full potential for quite some while.

Special Reconnaissance (SR)

So what is actually SR? [lix] The core activity Special Reconnaissance is defined as a mode of operations applied in order to “provide specific, well-defined, and possibly time-sensitive information of strategic or operational significance.”[lx] It is used to place “persistent ‘eyes on target’ in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive territory.”[lxi] SR can be used to “complement other collection methods where constraints are imposed by weather, terrain-masking, hostile countermeasures, or other systems’ availability.”[lxii] And SR can be done by using “advanced reconnaissance and surveillance techniques, JISR assets and equipment, and collection methods, sometimes augmented by the employment of indigenous assets.”[lxiii] Activities within SR can include Environmental Reconnaissance, Threat Assessment, Target Assessment, and Post-Strike Reconnaissance.[lxiv]

Unexploited Potential in SR

To exploit the full potential that lies within the complete Intelligence cycle (direction, collection, processing, and dissemination),[lxv] the use of SR and the deliberate use of women in different intelligence-collection roles have been, and will continue to be key. There are mainly two reasons for why using women for these roles is key when it comes to future SR operations.

- Psychological and Cultural Access.

Women may obtain unique access to information derived from other human beings, also known as human intelligence (HUMINT). There are at least three possible scenarios that where women may be the only ones able to gain access to unique information. First, when information can be accessed and derived only from other women, especially in cultures where only women can interact with other women. Here, the unique cultural access is relevant. Second, when the information can be accessed and derived from men who will reveal this information only to women. Here it is the unique psychological access that makes a difference. Third, when information can be accessed and derived from other human beings only by introducing women as a surprising element and exploiting the potential information-momentum this may cause, for example, during tactical questioning on a target or during interrogations in an appropriate facility. In situations like this, it is a combination of the different types of access that is relevant to this discussion. - Physical Access and Concealment.

Women may be able to get unique physical access to areas where they can collect information, through both HUMINT and observation or through other technical collection means. There are mainly three different scenarios where this could play out, but there are numerous of facets of these scenarios if the psychological and cultural access aspect is also taken into account. First, when the environment demands only female operators in order to avoid detection throughout the whole operation—during infiltration, the collection phase, and exfiltration. Second, when the environment demands only female operators in at least one of the phases of an operation in order to avoid detection. Three, when the environment demands female operator’s presence in one or more phases of the operation to avoid detection, as part of a mixed team.

SR History 1 - WWII

Throughout history, there are several examples of effective SR involving women in essential roles. One example is the operations conducted by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in France during WWII. In 1941, the SOE established a unit responsible for France as its area of operations (AO), Section F.[lxvi] When established, this unit consisted of both men and women, based on an analysis of the security environment of the time, which suggested to the SOE that gender roles in French society would affect the SOE’s operations. When the SOE recruited operators for this unit, the two most important selection criteria were French language skills and an operator’s ability to appear French.[lxvii] The environment of the time demanded men and women to act differently to fit in.[lxviii] For example, men who lived in rural areas were expected to be more socially active compared to women, something that made it more challenging for male SOE operatives to keep their cover compared to the female operatives. This led to women working for longer periods and gaining more intelligence without being compromised compared to men.[lxix]

SR History 2 - SR/FET in Afghanistan

Another example of SR involving women in essential roles is the use of Female Engagement Teams (FETs) in Afghanistan, which was initiated by the United States Marine Corps (USMC) in 2009–2010.[lxx] These teams consisted of female soldiers, NCOs, and officers. The intent was to“develop trust-based and enduring relationships with the Afghan women they [encountered] on patrols,”[lxxi] “in order to engage the female populace” in Afghanistan.[lxxii] Even though the FET concept has received criticism for having a vague mandate, personnel not being prepared for the task,[lxxiii] and for creating false expectations future Afghan governments cannot fulfill,[lxxiv] I believe that if the FETs had been prepared for the task before them and if these teams had been used as they were intended, these teams would have obtained physical access to areas, and psychological and cultural access to information, where men could not get access.

SR Roles that Demand Women

So, the partial conclusion here is that there are roles and tasks/missions within SR operations that demand women if an operation is to be executed successfully. There is a demand for a female SR-operator in several roles for SOF to be a relevant and effective tool for the future. The spectrum of roles stretches from being an individual operator who is the main effort during a SR-operation and who collects intelligence through HUMINT, observation, or other technical means on one end, to being an operator as a part of a team, who is only a supporting—but essential—asset gaining physical, psychological, or cultural access to information on the other end of the spectrum.

In part two we will investigate female advantages within DA (Direct Action) and MA (Military Assistance) before summarizing and concluding this article series.

Foto: FSK (Stig B. Hansen)

[i] NATO/IMS, “Committee on Women in the NATO Forces: Denmark,” 26 March 2002, http://www.nato.int/ims/2001/win/denmark.htm; RT Question More, “Girls in the Army: Norway Passes Bill on Mandatory Military Service,” 20 October 2014, https://www.rt.com/news/197152-norway-army-women-military-conscripts/; Aftenposten, “The Parliament Passes Bill for Mandatory Conscription for Women 14 June” (in Norwegian), 21 April 2013, http://www.aftenposten.no/norge/politikk/Stortinget-vedtar-verneplikt-for-kvinner-14-juni-121837b.html#.UXvu5Er-uSr; Rick Noack, “World: Swedish Military to Start Drafting Women to Help Fend Off Threats Such as Russia,” National Post, 6 October 2016, http://news.nationalpost.com/news/world/swedish-military-start-drafting-women-to-help-fend-off-threats-such-as-russia

[ii] United Nations, “UN Resolution 1325: Women, Peace, and Security,” 31 October 2000, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N00/720/18/PDF/N0072018.pdf?OpenElement

[iii]Frank G. Hoffman, “Hybrid Warfare and Challenges,” Joint Force Quarterly, 52, no. 1 (2009).

[iv]W. S. Lind, “Understanding Fourth Generation War,” Military Review(September-October 2004), 12–16.

[v]Ibid.

[vi] W. S. Lind, “The Fifth Generation of Warfare?” 3 February 2004, http://www.military.com/NewContent/0,13190,Lind_020304,00.html

[vii]Rupert Smith, The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World (London: Penguin Books, 2006), 267–69 and 270–78.

[viii] Ibid., 267–69 and 278–89.

[ix] Ibid., 267–69 and 289–92.

[x] Ibid., 267–69 and 292–97.

[xi] Ibid., 267–69 and 301–305.

[xii] Ibid., 267–69 and 297–301.

[xiii]Arthur K. Ellis, Teaching and Learning Elementary Social Studies (Allyn and Bacon, 1970), 431.

[xiv]David Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 107.

[xv]John Arquilla, Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits: How Masters of Irregular Warfare Have Shaped Our World(Lanham, MD: Ivan R. Dee, 2011), 270.

[xvi]Ibid., 279–80.

[xvii]Ibid., 269

[xviii]Ibid., 270.

[xix] Ibid., 276.

[xx] Ibid., 271.

[xxi] Ibid., 274.

[xxii] Ibid., 272.

[xxiii]Ibid., 279–80.

[xxiv] Martin van Creveld, Transformation of War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009), 197.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid., 194.

[xxvii]Smith, Utility of Force, 267–69 and 278–89.

[xxviii]Ibid., 267–69 and 270–78.

[xxix] Ibid., 267–69 and 289–92.

[xxx] Ibid., 267–69 and 292–97.

[xxxi] Ibid., 267–69 and 301–305.

[xxxii]Lind, “Understanding Fourth Generation War,” 12–16.

[xxxiii] The World Bank, “Population (Female % of Total),” October 2016, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.ZS. According to the World Bank, the world’s population of 2015 consisted of 7.34 billion people, 49.55% women and 50.45% men. In countries where open conflicts were ongoing, as in Afghanistan and Syria, the population consisted of respectively 48.4% and 49.4% women. In countries where low intensity conflict were on going or expected to erupt in the near future, like the African nations of Chad, Niger, and Cameroon, the population consisted of respectively 49.9%, 49.6% and 50% women.

[xxxiv]United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, “World Population Projected to Reach 9.7 Billion by 2050,” July 2015, http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/news/population/2015-report.html

[xxxv]Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains, 107.

[xxxvi]Ibid.

[xxxvii] Arquilla, Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits, 274.

[xxxviii]Ibid., 270.

[xxxix] Ibid., 276.

[xl] Ibid., 271.

[xli] Ibid., 272.

[xlii]Ibid., 270.

[xliii] Van Creveld, Transformation of War, 223.

[xliv] Ibid., 195.

[xlv] Jamille Bigio and Rachel Vogelstein, “Women Are Key to Counterterrorism—Investing in Women Will Go Further to Fight Terror than Donald Trump’s Refugee Ban Ever Will,” U.S. News, 8 February 2017, http://www.usnews.com/opinion/op-ed/articles/2017-02-08/women-are-critical-in-the-fight-against-terrorism-and-the-islamic-state ; Jamille Bigio and Rachel Vogelstein, “How Women’s Participation in Conflict Prevention and Resolution Advances U.S. Interests,” Council on Foreign Relations, October 2016, http://www.cfr.org/peacekeeping/womens-participation-conflict-prevention-resolution-advances-us-interests/p38416

[xlvi] Van Creveld, Transformation of War, 207.

[xlvii] Martin van Creveld, “Military Women Are Not the Cure, They Are the Disease,” 24 November 2016, http://www.martin-van-creveld.com/military-women-not-cure-disease/;Martin van Creveld, “To Wreck a Military,” Small Wars Journal, 28 January 2013, http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/to-wreck-a-military

[xlviii] Van Creveld, Transformation of War, 203.

[xlix] Ibid., 223.

[l]David Tucker and Christopher J. Lamb, United States Special Operations Forces (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 42.

[li] Ibid., 43.

[lii] United States Special Operations Forces Command, “SOF Truths,” 2016, http://www.socom.mil/about/sof-truths

[liii] Ibid.

[liv] NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine for Special Operations (AJP-3.5), Version A, 1st ed. (Brussels: NATO Standardization Agency, 2013).

[lv] Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, Special Operations (Joint Publication 3-05) (Washington, DC: Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2014).

[lvi] Tucker and Lamb, United States Special Operations Forces, 42.

[lvii] U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Special Operations: Task Force Operations (Joint Publication 3-05.1) (Washington, DC: DoD, 2007).

[lviii] F. B. Steder, Military Women: The Achilles of the Armed Forces? (in Norwegian). (Oslo: Abstrakt forlag, 2013), 56.

[lix] SR as it is defined in NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine for Special Operations: “SR is conducted by SOF to support the collection of a commander's Priority Intelligence Requirements (PIRs) by employing unique capabilities or Joint Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (JISR) assets. As part of the Allied theatre INTEL collection process, SR provides specific, well-defined, and possibly time-sensitive information of strategic or operational significance. It may complement other collection methods where constraints are imposed by weather, terrain-masking, hostile countermeasures, or other systems’ availability. SR places persistent ‘eyes on target’ in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive territory. SOF can provide timely information by using their judgment and initiative in a way that technical JISR cannot. SOF may conduct these tasks separately, supported by, in conjunction with, or in support of other component commands. They may use advanced reconnaissance and surveillance techniques, JISR assets and equipment, and collection methods, sometimes augmented by the employment of indigenous assets.”

[lx] NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine for Special Operations, 2-2.

[lxi] Ibid.

[lxii] Ibid.

[lxiii] Ibid.

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] NATO, Allied Joint Doctrine for Intelligence Counter Intelligence and Security (AJP 2), Edition A Version 1(Brussels: NATO Standardization Agency, 2014), 4-1, 4-2.

[lxvi] J. Pattinson, Behind Enemy Lines: Gender, Passing and the Special Operations Executive in the Second World War. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007).

[lxvii] Ibid., 25, 32.

[lxviii] Ibid., 61.

[lxix] Ibid., 70.

[lxx] U.S. Army, “Female Engagement Teams: Who They Are and Why They Do It,” 2 October 2012, https://www.army.mil/article/88366 , and NATO, “United States Marine Corps Female Engagement Team, presentation by 1st LT Zoe Bedell,” May 2011, http://www.nato.int/issues/women_nato/meeting-records/2011/pdf/BEDELL_FETPresentation.pdf

[lxxi] Ibid.

[lxxii] Ibid.

[lxxiii] Gary Owen, "Reach the Women: The US military´s experiment of female soldiers working with Afghan women" 20 June 2015, https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/reach-the-women-reviewing-the-us-militarys-experiment-with-female-soldiers-contacting-the-other-half-of-afghan-society/ (accessed 19 FEB 2017)

[lxxiv] Natalie Smbhi, “Female Engagement Teams in Afghanistan,” 15 February 2011, https://securityscholar.org/2011/02/15/female-disengagement-teams-in-afghanistan/ (accessed 19 FEB 2017)