When the T-14 Armata tank was sensationally unveiled at the 9 May Victory Day parade, in 2015, it embarrassingly broke down in front of thousands of onlookers during rehearsals. This proved an augury. Seven years later it can be stated with confidence the Armata story is over. This article explains its demise and wider implications.

An engine looking for a tank

The origins of T-14 Armata lie in the cancelled T-95 (Object 148). This tank, a casualty of the troubled 1990s, was finally abandoned in 2010. Conceptual vehicles with unmanned turrets had existed since the 1980s (CIA Top Secret ‘Soviet Tank Programs’, NI IIM 84-10016, 1 Dec 84 offers interesting historical perspectives on these designs). However, in the case of T-14 Armata the idea did not start from the cancelled T-95, or even a tank design, but with an engine.

Some context is necessary. All Russian tank engines, remarkably, are descended from the highly successful V-2 diesel engine designed in 1931 at the Kharkov Locomotive Plant (now destroyed by Russian forces). The V-84 (T-72s), V-92S2F (T-72B3s, T-90s), the UTD-20 (BMP-1s and BMP-2s), and UTD-29 (BMP-3s) are further upgrades of this engine. The V-2 is the Kalashnikov of tank engines. The exception to this practical Soviet approach is the T-64. This tank was fitted with the 5TDF engine, a failed attempt to copy a German wartime bomber engine. It is for this reason that the 2-3,000 T-64s in storage will never return to service.

T-14 Armata also started with a new engine: a Russian copy of the German X-shaped Simmering SLA 16 engine (also known as the Porsche Tour 212). The Russian engine was designated the A-85-3. However, Transdiesel Design Bureau did not design the engine for a tank but rather as a unit for compressor oil and gas pumping stations. It proved a flop and failed to make any sales despite repeated demonstrations at exhibitions.

Designed around the engine

By a roundabout and unclear route, Uralvagonzavod (UVZ) – Russia’s main tank manufacturer – decided to use the engine as the basis of a novel tank: the T-14 Armata. The tank was designed around the engine and not the other way round. It seemed a good idea: the A-85-3 was smaller and more powerful, if heavier, than the V-92S2F now fitted to the modern T-72B3s and T-90s. However, this decision had two important and deleterious consequences. The A-85-3 did not sell because it was complex, manifested too many problems, and was difficult to maintain. The engine needed many more run-hours to refine the design.

It is assumed UVZ was confident the problems would be rectified over time. They have not been and the A-85-3 remains a problem engine. The second consequence has followed from the size of the engine. A quick solution might have been to abandon the A-85-3 and refit T-14 Armata with the proven V-92S2F – except the latter does not fit, it is bigger. The only realistic engineering solution now is to start again. Currently, no authority appears willing to accept this reality.

An AliExpress tank

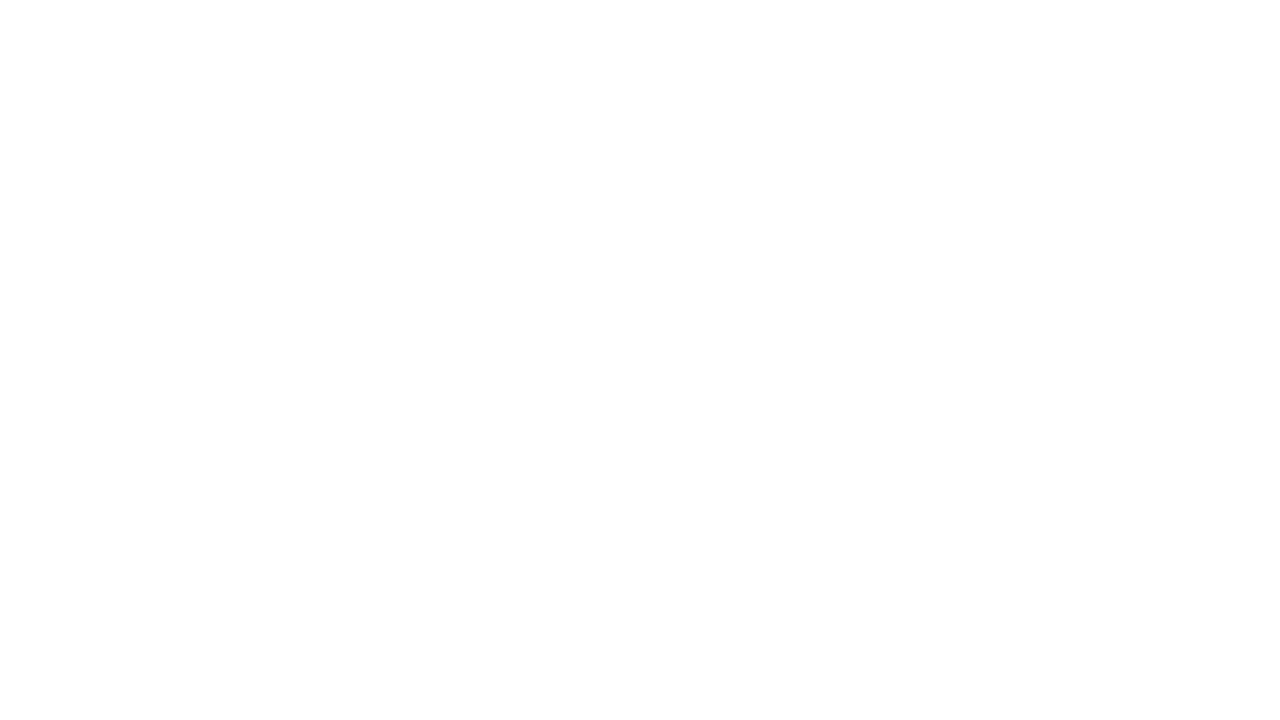

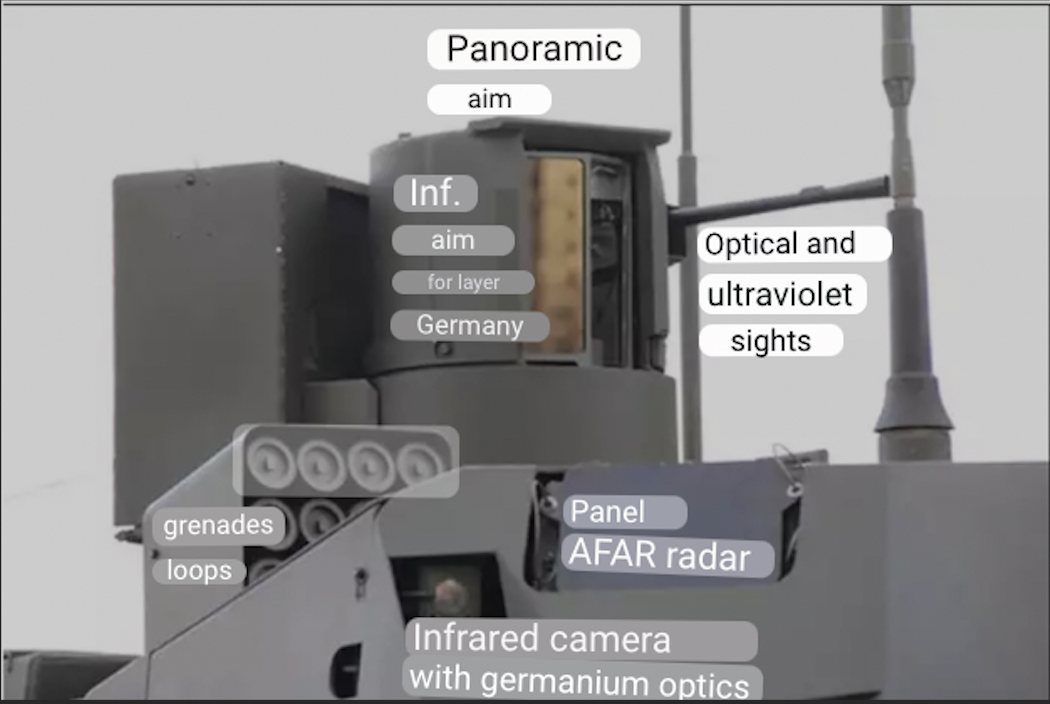

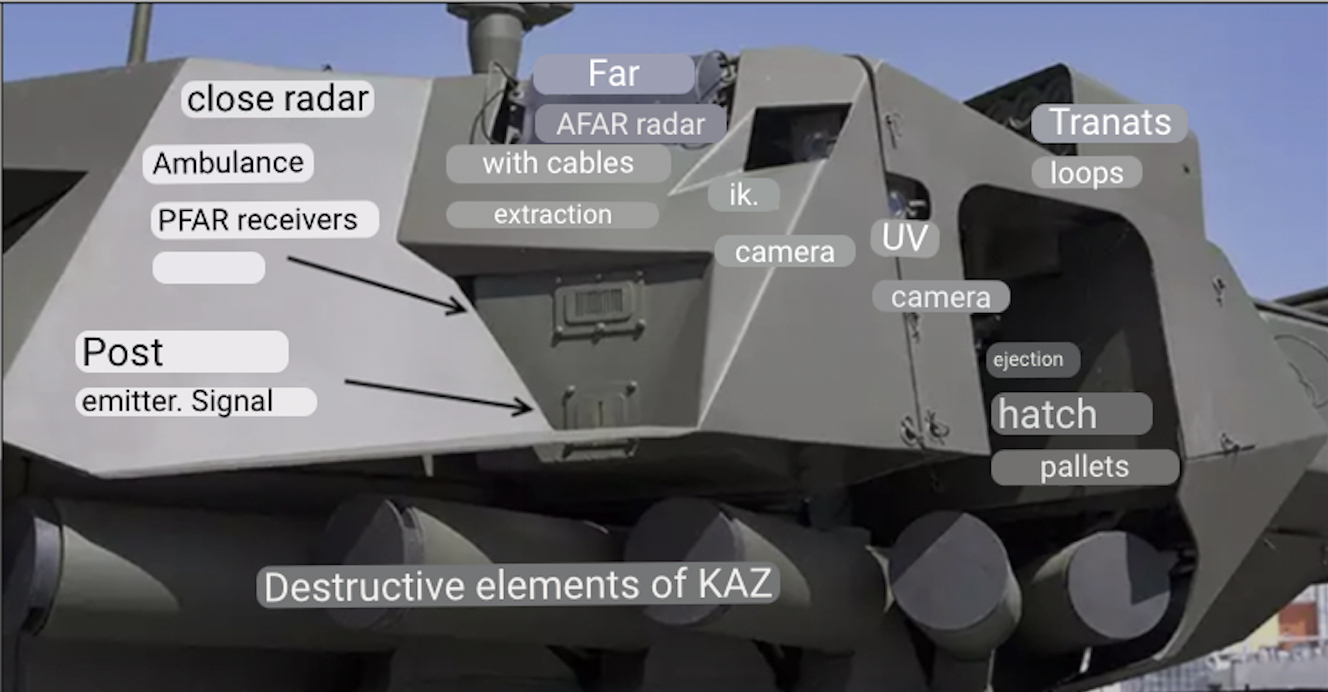

In July 2021, the Russian MOD television channel TV Zvezda broadcast a documentary on T-14 Armata under its ‘Military Acceptance’ strand. The programme was filmed at the normally secretive 38th NII BTVT which celebrated its 90th anniversary last year and remains Russia’s premier armoured vehicle trials facility. A viewer of the 30-minute slot was treated to a futuristic world including rare footage of the inside of the T-14 Armata crew capsule.

The problem with all the gizmos is the microelectronics. Russian industry generally has been critically dependent on foreign microelectronics and associated technologies. These are no longer available due to sanctions (hence the joke Russian defence’s main supplier has become AliExpress). Captured Russian equipment such as drones reveals components are being sourced from wherever they can be found (including stolen Swedish traffic cameras in the case of the Orlan-10 UAV).

The perennial Russian problem of corruption has only worsened challenges posed by sanctions. The Volgograd Krasny Oktyabr (‘Red October’) plant which makes the armour plates for Russian tanks was declared bankrupt in 2018. Millionaire-owner Dmitry Gerasimenko is on the international wanted list for allegedly embezzling a loan of $65 million and transferring 6.2 billion roubles abroad. Such tales litter Russian industry. Since 2011, a staggering 72,000 officials have appeared before the courts on corruption charges. In 2022 alone (so much for patriotism) 60 defence industry officials and 250 public procurement officials have been prosecuted, 27 of whom were convicted of violations in the implementation of the state defence order.

Lack of an assembly line

The final, practical and mundane reason why T-14 Armata will not become a production tank is because there is no assembly line. All models to date have been assembled by hand (like luxury cars). A sum of 64 million roubles was reportedly allocated to build the assembly line. The plant shell and workshops were built but are empty. Contracts were signed but Western machine tools and other technology were never supplied due to sanctions (the same story has now unfolded with Russia’s moribund automotive industry facing an uncertain future with the departure of Western and Far Eastern car manufacturers). As many as 200 suppliers would need to be re-profiled. This will not happen now.

As relevantly, UVZ is fully engaged in sustaining the T-72B3 and T-90M assembly lines, desperately needed to replace war losses (Omsktransmash, the other tank plant, is refurbishing T-62Ms). At the time of writing, at least 1,594 tanks have been lost including 448 T-72B3-series tanks, and 37 T-90-series tanks that remain rare in Ukraine. The Russian Army started the war with 2,600 operational tanks, of which around 1,000 were ‘modern’. It took UVZ roughly a decade to produce or upgrade the ‘modern’ fleet. It will take an equally long and probably lengthier time to recover Russia’s decimated tank regiments.

T-14 Armata, in the end, proved a story of technology over-reach. ‘The fact remains that the T-14 will remain a prototype toy with no chance of mass production’, Russian defence journalist Roman Skomorokhov has sentenced. The root problem with the engine means ‘the tank moves satisfactorily only under the cover of a group of technicians and engineers’. Only one experimental company was ever formed anyway in Central Military District (CVO) and the chances it will appear on a frontline, except for propaganda purposes, are small.

More than a novel tank is lost. In June 2015, The Royal United Services institute (RUSI) hosted an event on Armata, presented by the knowledgeable Ukrainian Igor Sutyagin. The talks highlighted the programme was about a family of ‘Armata’ vehicles (T-15 heavy IFV, T-16 BREM-T ARRV, K-25 Kurganets and others). It is highly unlikely any of these projects will now proceed in the near/mid-term or at all. The future looks much like the out-dated Soviet past. As a final blow T-14 Armata’s improved 2A82-IM 125mm cannon – an undeniable upgrade on comparatively under-gunned Russian tanks – will not serve on T-90M. The breech block doesn’t fit.